Reproducible academic manuscripts using GNU Make: Part 1

Welcome to this first tutorial on using GNU Make for reproducible research!

We are going to see how the Make tool can create cross-platform application agnostic workflows that will save time, encourage transparency and collaboration, and keep your code readable for many years. This tutorial is mostly geared for neuroscientists who use R and Matlab scripts but are looking to automate and share their analysis scripts.

What is GNU Make and why does it matter?

“Make” is one the most widely used methods to automate the creation of computer programs from source code. Make knows how to build a program from a text file called a Makefile. The Makefile has simple details on what your final target files should be and what source files are used to build them.

Make figures out (using date and time) which targets need to be updated based on what source files have changed. It can determine the proper order for updating a target file since some targets require other targets to properly build. Make doesn’t need to recreate every target file each time it is run. It updates only those target files that depend directly or indirectly on source files that you changed.

Make ethos: Printable, Debuggable, Understandable

Make was created in 1976 by Stuart Feldman, an intern at Bell Labs. He found a way to fix an age old software programming problem: ensuring you have an updated final product after multiple changes to source code. Make has been praised for its simplicity, and use of Makefiles are standard practice in computer science, in which complex programs must be build from hundreds, or even thousands, of pieces of source code!

What is an example of how Make can be used for research?

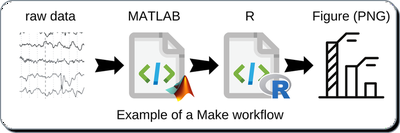

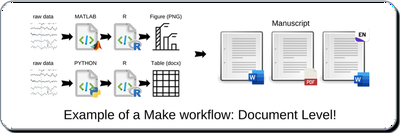

Make can be used at any level of your research workflow. For example, consider a publication figure as a target file, in this case a high-resolution image called Figure1.png.

- A MATLAB script that generates a CSV file with results from raw data.

- An R script that imports the CSV and summarizes the data

- An R script using ggplot2 to create and save a figure.

A simple Makefile would automate the generation of Figure1.png. Amazingly, Make can detect a change to a source file (i.e., MATLAB script or raw data) and perform each subsequent step to update the target file (i.e., Figure1.png).

What will I need to know in order to use Make?

Make doesn’t have any preference for any particular analysis language. You instruct Make (through the Makefile) what target files to watch for and instructions which source files are needed. Make is able to perform these tasks since every analysis software can create a target from a source using a command. The actual Make syntax or programming language are simple commands that can be learned in an afternoon.

To be more direct, you should continue to program your analyses in R, Python, or MATLAB. Using Make does not change what you program in! In fact, many people find that their original source code becomes more efficient and easier to read since Make forces you to consider the input and output of every source file.

Writing source code to use with Make

To efficiently use Make, your source code (in any programming language) should:

- be able to run without user intervention

- have clear input files (if needed)

- have a clear output file

For some researchers, this may already be your workflow. For others, especially if you are used to very long single code files, this might be an adjustment. Writing source code compatible with Makefile has one compelling advantage: since a Makefile contains a “recipe book” for how you put your code together, a reader (and your future self) know how every piece fits into the whole. The working code can be immediately uploaded to a repository, shared with a collaborator, or used by a remote computational cluster.

Who would best benefit from this tutorial?

The method below outlines a pragmatic approach to use Make for Neuroscientists primarily for writing publications or generating reports. In terms of goals:

- Eliminate the need to change analysis software

- Improve efficiency of how you write or share code

- Have readable, easily maintained code that is easy to test or reuse

What are the next steps?

If you are interested in seeing an example of Make in action in the setting of academic research, continue to part two of this tutorial!